UnitedHealth and Amedisys are finally on the same page as federal regulators.

The companies have been trying to merge since January 2023, though the Department of Justice held up the deal, arguing it would obliterate competition for home health and hospice services in certain U.S. markets. But under a new settlement between UnitedHealth, Amedisys and regulators disclosed Thursday, the $3.3 billion deal is now on a glide path to closure, according to experts.

“Given the fact that United is likely very eager to put this behind them, it’s more than likely to progress forward,” said Joe Widmar, director of mergers and acquisitions at consultancy West Monroe.

The agreement still needs to be approved by a judge after a public comment period. That, and other regulatory requirements around the settlement, mean the deal likely won’t close until 2026 at the earliest.

But the judge’s review is “rarely a tool to turn over a settlement,” said Robin Crauthers, a partner with law firm McCarter & English specializing in antitrust matters. “I think the settlement sticks and the parties close and we all just move on.”

Amedisys stock rose over Thursday’s trade after a DOJ press release announced the settlement, a “strong indication” that investors also think the transaction is in the home stretch, TD Cowen analyst Ryan Langston wrote in a note.

The deal’s tentative greenlight from the U.S. government is a welcome turn of events for UnitedHealth. The healthcare behemoth’s stock has plummeted this year as the company struggles with unexpectedly high medical spending for its insurance members, unfavorable policy changes from Washington and widespread public criticism over its business practices.

Amedisys, one of the largest home health and hospice providers in the U.S., is only going to be a modest contributor to UnitedHealth’s earnings, according to analysts.

Still, reaching a settlement with the DOJ over the deal removes a key source of regulatory uncertainty that’s dogged the company for more than two years. For UnitedHealth, it probably couldn’t have come at a better time.

“It’s not terribly surprising to see [a settlement] happen, especially given the year United has had. They’re probably looking for a bit of good news,” Widmar said.

Settlement may not preserve competition

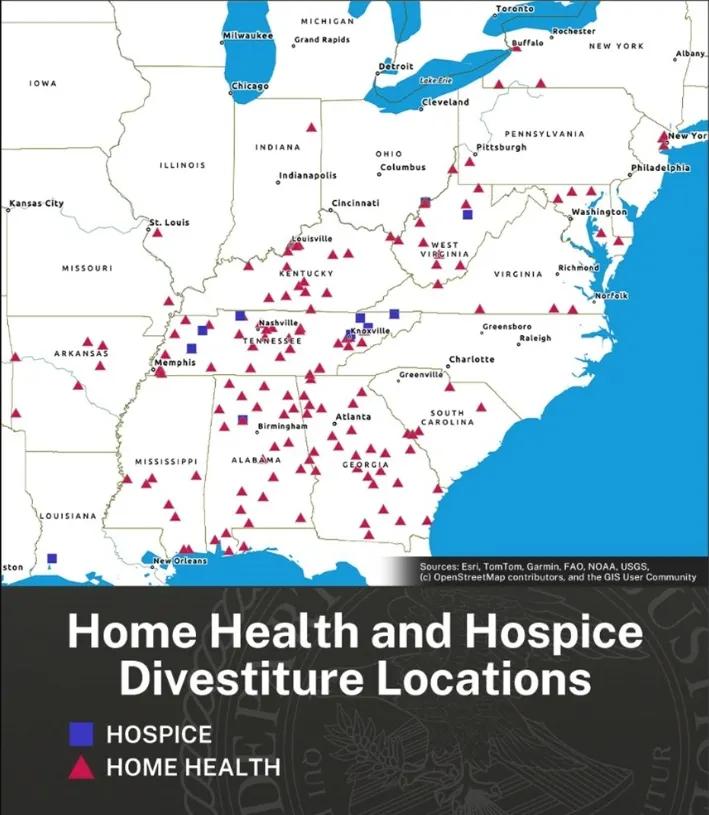

The settlement requires UnitedHealth and Amedisys to divest at least 164 home health and hospice sites for the DOJ to approve the deal. The lion’s share of divested assets provide home health.

Two midsize home health and hospice operators, BrightSpring Health Services and Pennant Group, have agreed to acquire the locations for an undisclosed amount.

Neither company responded to a request for more information, though TD Cowen analysts peg BrightSpring’s investment in the range of $200 million to $300 million and Pennant’s at around $100 million.

Other stipulations in the settlement force UnitedHealth and Amedisys to offload stakes in certain joint ventures, agree to monitoring of their divestiture plans and help clinics acquired by Bright and Pennant compete in markets overlapping with UnitedHealth.

Regulators think this is enough to offset the deal’s anticompetitive effects.

“This settlement protects quality and price competition for hundreds of thousands of vulnerable patients and wage competition for thousands of nurses,” Abigail Slater, assistant attorney general in the DOJ’s antitrust division, said in a statement Thursday.

It’s the largest divestiture of outpatient healthcare services to resolve a merger challenge ever, according to the DOJ.

Divested facilities are concentrated in the southeast, which makes sense given Optum’s heavy presence in the region following its acquisition of Amedisys’ competitor LHC Group in 2023, experts said.

But the settlement is weaker than expected based on the wide-reaching competitive concerns the DOJ outlined in its November lawsuit seeking to block the deal, according to McCarter & English’s Crauthers.

The DOJ’s complaint — which was joined by four states — said if the merger closed, UnitedHealth would control 30% or more of the home health or hospice market in eight states, while expanding for the first time into an additional five states. UnitedHealth would gobble up the home health market to a degree that made the merger presumptively illegal in hundreds of local markets, regulators said.

The DOJ’s complaint, which was issued by the Biden administration, outlined nearly 800 home health and hospice markets that would see competition lessen as a result of the Amedisys deal, according to Crauthers.

Many of those markets weren’t addressed in Thursday’s settlement, which comes from the more business-friendly Trump administration, she said.

“A settlement is supposed to remedy the alleged substantial lessening of competition. I’m not sure this settlement goes far enough — and that’s based on the complaint,” Crauthers, who worked at the DOJ for six years, said. “I don’t want to make it sound like it’s bad, but if you take the complaint at face value the DOJ has taken less than it intended.”

Past divestiture plans proposed by UnitedHealth and Amedisys didn’t pass regulators’ muster. Last summer, the companies outlined plans to sell assets to VCG Luna, a subsidiary of Texas home health and hospice company VitalCaring Group — but that fell through after the DOJ said VCG Luna was unreliable.

Another plan to sell assets to BrightSpring and Pennant this spring was also initially rejected by the DOJ, according to a CTFN report.

The DOJ did not respond to a request for comment on how the new settlement differs from past proposals.

According to Widmar, the settlement looks like it should preserve the competitive status quo in the markets that do include the 164 divested locations — though it places businesses worth almost $530 million in revenue in the hands of BrightSpring and Pennant. Both are already “rather large players,” he said.

“I wouldn’t expect the number of locations to necessarily tip the scales,” Widmar said. “The greater concern, I would imagine, has been the fact that United as a vertically integrated health insurer is attempting to deepen in the home health space.”

Vertical integration play

UnitedHealth is a diversified healthcare giant, with the largest private insurer in the country, a major physician network and other businesses that together exceed $400 billion in annual revenue.

Further building up care delivery — including by acquiring players in the highly fragmented home health market — is a key prong of UnitedHealth’s strategy. The company says that acquiring Amedisys will help it serve customers at the lowest cost and most convenient site of care, resulting in better outcomes.

“On average, patients who receive home health care are readmitted to a hospital 36% less than patients who do not receive home health care,” according to a website hosted by UnitedHealth’s health services division Optum.

Providing such care could also prove lucrative as the U.S. population ages, which should increase demand for home-based care models.

Adding more home health capabilities is also useful for how those assets interact with UnitedHealth’s health insurance business, UnitedHealthcare.

By nudging its members towards in-house and low-cost settings, UnitedHealth can curb health benefits spending while reimbursing its provider subsidiaries for providing that care — essentially paying itself for the service.

That overlap has become a font of revenue for the company. UnitedHealth’s intercompany eliminations — essentially, how much revenue UnitedHealth pays its subsidiaries for providing services to its own insurance members — reached $150.9 million in 2024, up 11% year over year. (This strategy also lets UnitedHealth sidestep profit caps in its insurance division — its provider businesses have no such restriction.)

In addition, home health assets allow UnitedHealthcare to peek into beneficiaries’ homes and communities, giving it a clearer picture of how they live, eat and get around outside of the doctor’s office. That information translates into a greater awareness of members’ needs, which UnitedHealthcare can use to prevent negative downstream health outcomes by investing in targeted preventive care.

It also allows UnitedHealthcare to collect more diagnosis codes. Such codes are inherently valuable in the Medicare Advantage program, in which insurers’ reimbursement from the government is adjusted based on the health needs of seniors in their plans.

That incentivizes insurers to collect and report as many codes as possible, even when that might exaggerate how sick their members actually are.

UnitedHealthcare generated $14 billion in MA overpayments through this practice, called upcoding, in 2021, according to a study published this year. That was by far the largest amount of any payer in the privatized Medicare program.

Home health is a major driver of upcoding. The health risk assessments and chart reviews that insurers provide in members’ homes contribute to 7% higher risk scores on average, according to a study published last year in Health Affairs.

In February, the Senate Judiciary Committee asked UnitedHealthcare for more information about its own at-home health risk assessment program after the HHS Office of the Inspector General found the payer was raking in more money from the government for diagnoses only made during the reviews than any other MA insurer.

UnitedHealth, which denies allegations of inappropriate coding, said in June that it supported greater federal oversight of at-home health risk assessments. The Department of Justice is currently investigating UnitedHealth over its Medicare billing practices.

In a statement, a UnitedHealth spokesperson said the company would continue to make improvements in the home health and hospice care space, calling it a “vital part of our value-based care approach.”

“We remain committed to delivering high-quality, compassionate care to the people and families who rely on us,” the spokesperson said over email. “We’re pleased to have reached a resolution and are grateful for the Department of Justice’s cooperation.”