LAS VEGAS — The window for digital health initial public offerings has opened after a long period of stagnation, but the outlook isn’t entirely smooth for firms looking to make the leap to the public markets, experts said at the HLTH conference this week.

Few digital health companies have entered the public markets in recent years, in sharp contrast to a surge of health technology IPOs in 2021. However, many firms that went public during the pandemic-era funding boom struggled in the spotlight — and some collapsed altogether.

There’s plenty of uncertainty in healthcare right now, making it more challenging for companies to decide to make a move, Robbert Vorhoff, managing director and global head of healthcare at private equity firm General Atlantic, said during a panel discussion at HLTH.

For example, the federal government shutdown is currently stretching into its fourth week and preventing the Securities and Exchange Commission from reviewing new IPOs. Meanwhile, the healthcare sector is bracing for the impact of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which will likely remove millions of people from insurance coverage and add new financial strain on providers.

That creates a more difficult environment for companies, which need to meet and exceed expectations set during the IPO process in their early quarters on the public markets, Vorhoff said.

“If there’s uncertainty, it’s very hard for management teams to commit to do that,” he said. “And the most precarious time I think in the growth of that company, the maturation that helps with the value creation of that business, is as a new public company.”

Still, there’s a lot of pent-up demand among established digital health startups to make an exit, experts say.

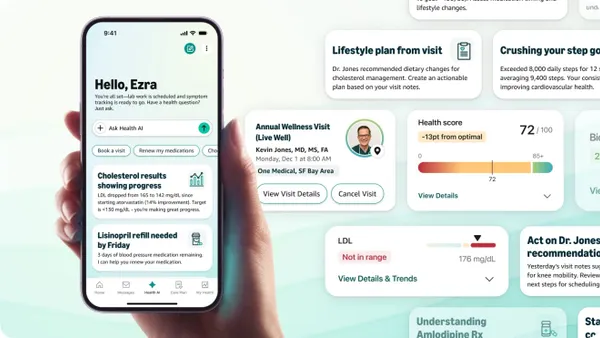

The sector has seen some bright spots recently. Healthcare payments firm Waystar went public in 2024. And earlier this year, digital musculoskeletal care company Hinge Health and chronic condition management firm Omada Health both hit the public markets.

“We know a lot of companies who are very excited about the possibility of going public in 2026 and 2027,” said Megan Scheffel, head of credit solutions for life science and healthcare at Silicon Valley Bank. “There are companies who are ready. There are companies I think who have the financial profile to go public if the market opens.”

The Omada, Hinge blueprint

Watching Omada and Hinge “redefined the blueprint of what it could take to be a public company,” Sasha Kelemen, a director in Baird’s global healthcare investment banking group, said during a panel.

Both firms generated attractive top line growth and margins, and demonstrated they were either profitable or on a path to profitability, she said.

Acting like a public company when you’re still private helped them prepare, leaders of Omada and Hinge said at HLTH.

Hinge tried to run its business like a public company for two years before its IPO, doing mock earnings calls and deciding the firm had to beat and raise expectations for four quarters before going public, said Daniel Perez, the company’s CEO and co-founder.

And when pitching investors ahead of an IPO, companies should try to get specific feedback on their businesses instead of solely trying to find the most optimal time to hit the public markets, Sean Duffy, co-founder and CEO of Omada, told Healthcare Dive.

“I just had enough investors say, ‘We would love this to come to market,’” he said. “And you have one say that, you have two say that, you have 10 say that, you have 20 say that. You’re like, ‘Okay, it’s ready.’”

M&A on the rise

Going public is a high bar to meet — requiring more costs, restrictions and scrutiny from shareholders — so it can’t be the goal for all companies, experts say. More firms will likely be able to pursue a different exit by being acquired by a larger company.

This year, mergers and acquisitions are increasing, largely through startups buying other startups, according to Rock Health. Deal volume increased 37% over last year, with the sector recording 166 acquisitions through the third quarter compared with 121 in 2024.

Some companies are consolidating, combining two similar firms to build efficiency, Scheffel said. Others are combining with adjacent businesses to add new capabilities. For example, a behavioral health company could merge with a physical therapy provider.

However, integrating two companies can be challenging, particularly for startups that have never embarked on M&A before, experts said.

“Now we are seeing a kind of come to Jesus moment generally, where a lot of companies are realizing across digital health broadly as well, that if they’re going to survive, or if the legacy was going to survive, they might have had to come together in different ways,” Kelemen said. “But it is a painful process to do that.”