Dive Brief

- CVS may have violated federal antitrust laws by preventing independent pharmacies from working with rival pharmacy service companies that it viewed as a competitive threat, according to a new report from the House Judiciary Committee.

- In late 2024, House Republicans opened an investigation into CVS’ relationships with pharmacy hubs, third-party companies that provide a range of digital pharmacy services to increase price transparency and patient access to drugs.

- According to thousands of internal documents CVS provided to the committee, CVS changed its network rules and weaponized audits and cease-and-desist letters to ensure independent pharmacies couldn’t work with competing hubs — at the same time as CVS was striving to build its own hub business, the Judiciary Committee said. CVS said it disagreed with the report’s findings.

Dive Insight:

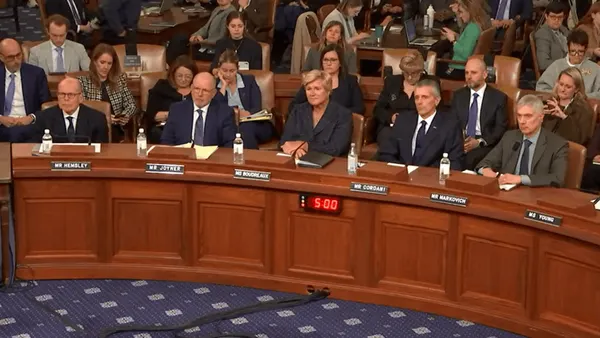

The Judiciary Committee released its report Wednesday amid a flurry of hearings on the Hill digging into why healthcare is so unaffordable in the U.S. One theme that emerged in the hearings on Wednesday and Thursday was anger over massive healthcare conglomerates that appear to be restricting market competition to benefit their own businesses.

A lot of flak was directed at major publicly traded insurers that also operate powerful middlemen in the U.S. drug supply chain, such as CVS. Now, the Judiciary Committee’s report — based on more than 2,200 proprietary CVS documents, including internal strategy memos, audit records, provider manuals and more — highlights how the company may have leveraged its market power to foreclose competitors in the pharmacy-as-a-service space.

Pharmacy-as-a-service has grown steadily in the past decade as pharmacies, pharmacy benefit managers and others in the sector recognized the need for better software and care coordination to increase efficiency and improve patients’ access to medication.

CVS’ PBM, Caremark, wanted to establish its own suite of pharmacy services to compete with digital hub pharmacies like Blink Health, Carepoint and GoodRx’s VitaCare, which work as the central point between multiple parties involved in a drug’s path from doctor to patient, according to the Judiciary Committee’s report.

But instead of competing with these other hubs on merit, CVS instead campaigned to prevent independent pharmacies from using them, the report alleges.

CVS did so by monitoring when independent pharmacies were contracting with other hubs and modifying its provider manuals — lists of rules pharmacies have to follow to participate in Caremark’s network. The changes essentially prohibited independent pharmacies from working with hubs, the report says.

CVS then used the modified manual as a pretext for auditing independent pharmacies and sending dozens of cease-and-desist letters to pharmacies that worked with other hubs, the Judiciary Committee found.

If independent pharmacies continued working with third-party hubs, Caremark warned they would be removed from its network — a significant threat, given that pharmacy would lose access to the tens of millions of insured Americans who receive drug benefits through the PBM.

House Republicans found “a string of cases where CVS Health followed a standard playbook,” the report says.

Investigators cited CVS’ behavior against Blink, a particularly prominent hub.

“When Blink partnered with a new independent pharmacy, CVS Health followed shortly thereafter with a cease-and-desist letter, threatening network termination if the independent pharmacy did not sever ties with Blink,” the report said. “Any independent pharmacy that chooses Blink over CVS Health could lose the ability to serve the approximately 30 percent of insured Americans that are in the CVS Caremark’s network.”

“CVS Health’s tactics could be detrimental to an entire geographic community,” the report concludes. Unless the pharmacy “stops working with a rival hub, CVS Health may take away a community’s access to medication.”

CVS told House investigators that it was working to remove drugs with exaggerated or “hyperinflated” prices from its formularies and root out fraud. However, the Woonsocket, Rhode Island-based company failed to provide any evidence of actual fraudulent behavior on the part of independent pharmacies of third-party hubs, the Judiciary Committee said.

Moreover, in May 2025 CVS started allowing certain independent pharmacies to work with other hubs, saying it had concluded that there’s minimal risk of fraud. But internal CVS documents “do not support [that] narrative,” the report says, suggesting that CVS reversed course in the face of congressional scrutiny.

A CVS spokesperson called the report “misguided, misleading, and inaccurate” in a statement.

“CVS Caremark works to make prescription drugs more affordable in the United States, while ridding the pharmaceutical supply chain of potential fraud, waste, and abuse,” the company said. “We are not opposed to pharmaceutical hubs or other innovative models that improve the patient experience. In fact, last year we updated our provider manual to make it easier for pharmacies in our network to use them.”

Criticism of major PBMs has been steadily increasing, with regulators and legislators in particular worried about intense concentration in the sector. The three largest PBMs — CVS’ Caremark, UnitedHealth’s Optum Rx and Cigna’s Express Scripts — jointly control about 80% of the market for PBM services.

The middlemen maintain they save money for both their clients and the healthcare system writ large, and blame high list prices set by pharmaceutical manufacturers for sky-high drug costs. But PBM giants have been accused of driving up list prices to increase their own profits, which are historically based on how much in pharmaceutical savings they can negotiate.

PBMs also take in money through a practice called “spread pricing,” wherein the middlemen reimburse pharmacies less for dispensing a drug than plan clients pay for it, and pocket the difference. Spread pricing has been cited as a factor for growing independent pharmacy closures nationwide.

Antitrust regulators have increasingly focused on how the “Big Three” PBMs could be leveraging their market power to profit. The Federal Trade Commission is currently suing Caremark, Optum Rx and Express Scripts for allegegly inflating the cost of insulin, though the lawsuit is on pause while agency considers a proposed settlement from Express Scripts.

Meanwhile, PBM reform is one health policy area with uncommon agreement between Republicans and Democrats. A package that would fund the government for the 2026 fiscal year includes some provisions cracking down on the companies, including delinking their compensation in Medicare’s prescription drug program from being tied to the list price of a drug.